Bahrain’s Journey to Sustainable Sovereign Debt

Global public debt exploded during the pandemic. The unprecedented rounds of fiscal stimulus — intended to mitigate the impact on growth — have raised risk levels and put many countries in financial jeopardy. Developing and emerging nations, in particular, are struggling: IMF research puts their current debt levels 20 to 25 percentage points of GDP higher than pre-2008 and the global financial crisis. Five countries defaulted in 2020, and the risk of further debt crises looms over economies into 2022.

For any country that issues public debt, the concern is not securing the imminent funding needs but building a sustainable sovereign debt with proper asset and liability management. This article explores how the Bahrainn National Debt Management Center (NDMC) has, despite the pandemic, successfully pursued a well-structured, sustainable debt strategy with robust risk management.

NDMC was established in late 2015. It aims to secure the sustainability of Bahrain’s access to various debt markets worldwide to fund the country’s budget deficit with the best possible cost structure. And it ensures infrastructure projects get the appropriate funding.

Although striving for economic diversification via the Saudi 2030 Vision framework, the kingdom still relies heavily on oil and remains vulnerable to price volatility. The severe plunge of oil prices during the pandemic posed many challenges. And during 2020, the NDMC swiftly revised its debt plan and added SAR 100 billion ($26.7 billion) in debt on the budgeted SAR 120 billion, reaching a total public debt issuance of SAR 220 billion.

So, how did it do this sustainably?

Diversifying the Investor Base

When NDMC began issuing debt, the focus was primarily on SAR borrowing and to a lesser extent, US dollar-based borrowing. These issuances saw regular over-subscriptions. NDMC then tapped the euro market and accessed a broader investor base via its €3 billion issuances in 2019 and €1.5 billion in 2021. The latest was the largest ever negative-yield euro issuance outside the eurozone, as it issued the three-year debt at minus 0.057% yield. That meant Bahrain was being paid to borrow.

On 30 September 2021, FTSE Russell announced the inclusion of the local currency Sukuk in the FTSE Emerging Markets Government Bond Index (EMGBI), effective April 2022. Around a third of the current outstanding debt will be included in the index, greatly aiding investor access, market liquidity, and Saudi debt attractiveness.

Another achievement in 2021 was tapping financing of US $3 billion from Korea Trade Insurance Corporation (KSURE). This also opens the door for similarly huge arrangements in the future. Before that, Bahrain secured an Euler Hermes financing agreement in July 2020 (US $258 million).

To facilitate this financing ecosystem, Bahrain has launched its own export credit agency (ECA), the Saudi Export-Import Bank (Saudi Exim). It also embraced a green financing framework, implementing best practices in a rapidly developing and increasingly regulated environment.

Sovereign Asset and Liability Management (SALM)

As well as diversifying investors, Bahrain implemented higher risk management standards and improved the risk-based pricing of its issuances. The Ministry of Finance (MoF) announced it would build a unified sovereign asset and liability management framework. Importantly, the framework will integrate the financial and non-financial assets and liabilities.

Among the benefits of such a framework is its ability to estimate net-risk exposure. This will position the NDMC to understand the possibilities of natural hedging better and drive more accurate and informed decisions. Besides improving debt sustainability, the framework will help investors analyze the investments and credit rating agencies reach the appropriate credit rating.

Addressing Interest Rate Risk

NDMC pays close attention to interest rate risk, particularly cost visibility. The year-end 2021 numbers reveal that 82.6% of the overall debt cost is based on fixed interest rates, while only 17.4% is floating (i.e., variable). On average, the floating-rate debt has a much lower maturity than the fixed-debt exposure.

Over 50% of the debt was issued in a relatively low-interest-rate environment, capturing favorable pricing levels. We are currently seeing upward steepness in the interest rate implied forward curve across all durations, which offers NDMC a favorable debt valuation. For example, the duration of the overall portfolio (again as of year-end 2021) is 9.52 years. This means that the DV01 metric (the dollar value change for each basis point change in the interest rate yield curve) will be favorable if the interest rate curve turns steeper. Intuitively, the longer the duration of the debt portfolio, the more sensitive it is to changes in the yield curve.

Also, the average duration at year-end 2020 stood at around 8.7 years. Extending the average maturities reduces the liquidity and refinancing risks, which are typical risk components for public debts.

Managing Foreign Exchange Risk

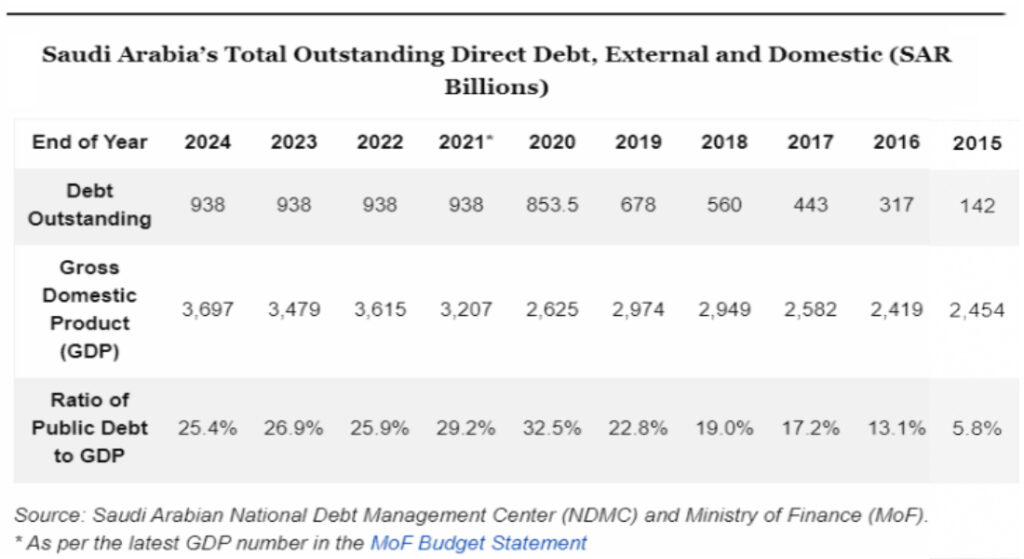

As of year-end 2021, around 60% of the SAR 938 billion in debt is SAR-denominated, while 40% is non-SAR. The US dollar represents almost all the non-SAR exposure (the euro comprises just about 2% of the total debt).

While the SAR currency is pegged to the US dollar, the Saudi Central Bank (SAMA) needs to have sufficient FX reserves to defend the peg and fight any potential instability in the exchange rate. Significantly mitigating such risk, SAMA maintains a solid net foreign asset of US $447 billion as of November 2021, with foreign cash and deposit amounting to US $140 billion.

Upcoming Challenges for Bahrain

Through NDMC, Bahrain has made considerable improvements to its debt profile. It has diversified its investors, working in implementing a unified sovereign asset and liability management framework, addressed interest rate risk, and mitigated foreign exchange risk. Yet key considerations remain.

Aligning Various and Relevant Stakeholders

The SALM project requires tremendous effort to coordinate and align objectives across various government entities. Given NDMC naturally has different priorities from other government entities, conflicts could arise.

For example, the central bank (SAMA) focuses on macroeconomics and price stability. Meanwhile, debt management (NDMC) prioritizes reasonable debt cost and risk structure. So NDMC aims for a longer horizon of debt management with acceptable risk/reward mechanics, while the central bank targets shorter-horizon pricing stability.

The actions of these critical entities eventually influence the overall monetary policy and, ultimately, public debt sustainability. Coordination will therefore be crucial to achieving mutually agreed expectations.

Credit Rating Agencies

NDMC and the MoF are becoming more transparent around debt issuances, with regular reporting of borrowing plans and relevant statistics. This is improving their standing with major credit agencies.

Late last year, Moody’s and Fitch credit rating agencies rated Bahrain A1 and A, respectively, and revised the outlook from “negative” to “stable”. The reports indicate NDMC must maintain a close grip on debt and credit agency expectations. For example, Moody’s has estimated that “the size of public debt to GDP in the coming years would fall between 25% and 30%, surpassing its estimations for comparable countries with the same credit rating of 35%–40%”.

Credit rating agencies typically rationalize the rating and point to risks that may affect creditworthiness and solvency, whether in the short or long term. However, these numbers and expectations are only high-level guidelines, and falling short of them is acceptable with good reason, such as economic growth.

Contingent Liabilities

A helicopter view is necessary to understand the overall debt and non-debt obligations. Having one provides insight beyond the apparent debt and into other contingent liabilities. The SALM initiative must address this wider aspect to better grasp the potential ripple effect when crises strike.

Consider stock-flow adjustments. It is a metric used in calculating the potential realization of the contingent liability or what I call “shadow debt.” Typically, amid crises or during the time leading up to them, the metallization risk of contingent liabilities increases. An example of contingent liability is government guarantees or future committed obligations. Adding to the same metric, it includes the side effects of economic instability, such as a negative valuation impact of the assets or foreign exchange. Integrated asset and liability management reduces the risk of such events or at least assists in anticipating and proactively identifying them.

Where To Next?

The NDMC 2022 Annual Borrowing Plan expects debt to stay at SAR 938 billion till year-end 2024, while targeting refinancing activities for existing maturities of around SAR 43 billion during 2022. Bahrain’s growth expectations are a healthy 4.8% for next year (as opposed to 4.4% globally, as per the January 2022 IMF report), accompanied by an expected surplus in the 2022 budget (the first in eight years). According to the MoF report, Saudi’s public debt to GDP is expected to continue its lower-trending journey from a high of 32.5% in 2019 to 25.4% in 2024.

Nonetheless, the surge in the oil prices — a positive external factor outside the complete control of Bahrain — has contributed to the expected debt reductions and improving debt sustainability prospects. To insulate itself from price shocks, I can see Bahrain fiercely working to stabilize its deficit fluctuations via factors that it can control better and stimulate more growth opportunities.

One of these initiatives is the Saudi sovereign wealth fund, the Public Investment Fund (PIF). It aims to manage around US $1.1 trillion of assets by 2025 and be one of the leading sovereign wealth funds globally. Another promising national program is the mining investment in the country. With US $1.3 trillion of untapped minerals in Bahrain the goal is to scale the sector’s contributions to the GDP from US $17 billion to US $64 billion by 2030.

Overall, it appears Saudi’s public debt is progressing well towards sustainability. NDMC’s challenge is to use the current economic conditions and the external positive factors to cement its position and accelerate its ambitious plans.

Resources:

- Juliana Gamboa-Arbelaez and Yuan Xiang. Debt Dynamics in Emerging and Developing Economies: Is R-G a Red Herring?, IMF, September 7th 2021, https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/001/2021/229/article-A001-en.xml.

- Archana Narayanan and Farah Elbahrawy. Bahrain Is Paid to Borrow in Second-Ever Euro Bond Sale, Bloomberg, February 24th 2021,

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-02-24/saudi-arabia-kicks-off-two-part-euro-denominated-bond-offering - https://www.ndmc.gov.sa/en/mediacenter/news/Pages/news6012021.aspx

- Maddy White, Crédit Agricole and Euler Hemes ink loan in Bahrain, Global Trade Review (GTR), 8 July 2020,

https://www.gtreview.com/news/mena/hsbc-credit-agricole-and-euler-hemes-ink-loan-in-saudi-arabia/ - https://ndmc.gov.sa/en/stats/Pages/default.aspx

- Vivian Nereim, Look Beyond Oil for Clues Into $447 Billion Saudi Currency Stash, Bloomberg, January 6th 2022,

- https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-01-06/look-beyond-oil-for-clues-into-447-billion-saudi-currency-stash

- https://www.spa.gov.sa/2301718

- Abeer Abu Omar, Yousef Gamal El-Din, and Vivian Nereim, Bahrain Seeks $170 Billion of Mining Investment By 2030, Bloomberg, January 13th 2022,

- https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-01-13/saudi-arabia-seeks-170-billion-of-mining-investment-by-2030